Featured Journal Content

Editor’s Note:

We feature three journal articles of particular interest below. The first two were selected for their pandemic focus and their timing as we seem to be slipping into a dangerous and evidence-devoid “post-pandemic mindset [as least in the Global North]. The third was selected based on the continuing and apparently intractable “zero-dose” children challenge and the article’s analysis of how this plays out across ethnic groups.

medRxiv

This article is a preprint and has not been certified by peer review [what does this mean?]. It reports new medical research that has yet to be evaluated and so should not be used to guide clinical practice.

Model-based estimates of deaths averted and cost per life saved by scaling-up mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in low and lower-middle income countries in the COVID-19 Omicron variant era

Alexandra Savinkina, Alyssa Bilinksi, Meagan C Fitzpatrick, A David Paltiel, Zain Rizvi, Joshua A Salomon, Thomas Thornhill, Gregg S. Gonsalves

doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.08.22270465

Posted February 09, 2022

Abstract

Background:

While almost 60% of the world has received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, the global distribution of vaccination has not been equitable. Only 4% of the population of low-income countries has received a full primary vaccine series, compared to over 70% of the population of high-income nations.

Methods:

We used economic and epidemiologic models, parameterized with public data on global vaccination and COVID-19 deaths, to estimate the potential benefits of scaling up vaccination programs in low and lower-middle income countries (LIC/LMIC) in 2022 in the context of global spread of the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV2. Outcomes were expressed as number of avertable deaths through vaccination, costs of scale-up, and cost per death averted. We conducted sensitivity analyses over a wide range of parameter estimates to account for uncertainty around key inputs.

Findings:

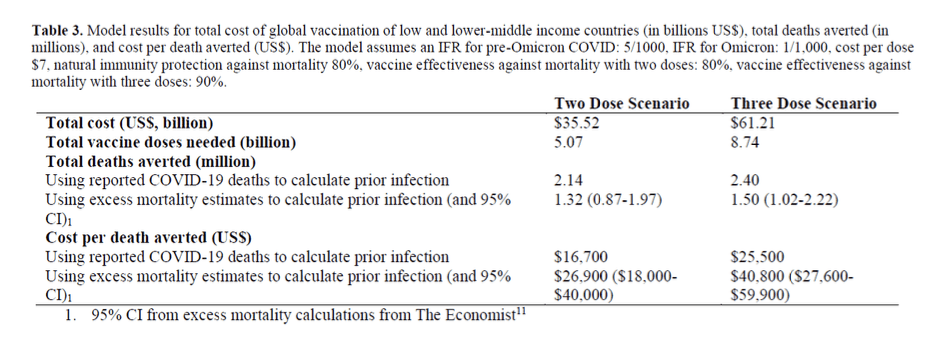

:: Global scale up of vaccination to provide two doses of mRNA vaccine to everyone in LIC/LMIC would cost $35.5 billion and avert 1.3 million deaths from COVID-19, at a cost of $26,900 per death averted.

:: Scaling up vaccination to provide three doses of mRNA vaccine to everyone in LIC/LMIC would cost $61.2 billion and avert 1.5 million deaths from COVID-19 at a cost of $40,800 per death averted.

:: Lower estimated infection fatality ratios, higher cost-per-dose, and lower vaccine effectiveness or uptake lead to higher cost-per-death averted estimates in the analysis.

Interpretation:

Scaling up COVID-19 global vaccination would avert millions of COVID-19 deaths and represents a reasonable investment in the context of the value of a statistical life (VSL). Given the magnitude of expected mortality facing LIC/LMIC without vaccination, this effort should be an urgent priority.

::::::

The Lancet

Articles| Online First

Pandemic preparedness and COVID-19: an exploratory analysis of infection and fatality rates, and contextual factors associated with preparedness in 177 countries, from Jan 1, 2020, to Sept 30, 2021

COVID-19 National Preparedness Collaborators

Open Access Published: February 01, 2022

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00172-6

Summary

Background

National rates of COVID-19 infection and fatality have varied dramatically since the onset of the pandemic. Understanding the conditions associated with this cross-country variation is essential to guiding investment in more effective preparedness and response for future pandemics.

Methods

Daily SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 deaths for 177 countries and territories and 181 subnational locations were extracted from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation’s modelling database. Cumulative infection rate and infection-fatality ratio (IFR) were estimated and standardised for environmental, demographic, biological, and economic factors. For infections, we included factors associated with environmental seasonality (measured as the relative risk of pneumonia), population density, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, proportion of the population living below 100 m, and a proxy for previous exposure to other betacoronaviruses. For IFR, factors were age distribution of the population, mean body-mass index (BMI), exposure to air pollution, smoking rates, the proxy for previous exposure to other betacoronaviruses, population density, age-standardised prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cancer, and GDP per capita. These were standardised using indirect age standardisation and multivariate linear models. Standardised national cumulative infection rates and IFRs were tested for associations with 12 pandemic preparedness indices, seven health-care capacity indicators, and ten other demographic, social, and political conditions using linear regression. To investigate pathways by which important factors might affect infections with SARS-CoV-2, we also assessed the relationship between interpersonal and governmental trust and corruption and changes in mobility patterns and COVID-19 vaccination rates.

Findings

The factors that explained the most variation in cumulative rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection between Jan 1, 2020, and Sept 30, 2021, included the proportion of the population living below 100 m (5·4% [4·0–7·9] of variation), GDP per capita (4·2% [1·8–6·6] of variation), and the proportion of infections attributable to seasonality (2·1% [95% uncertainty interval 1·7–2·7] of variation). Most cross-country variation in cumulative infection rates could not be explained. The factors that explained the most variation in COVID-19 IFR over the same period were the age profile of the country (46·7% [18·4–67·6] of variation), GDP per capita (3·1% [0·3–8·6] of variation), and national mean BMI (1·1% [0·2–2·6] of variation). 44·4% (29·2–61·7) of cross-national variation in IFR could not be explained.

Pandemic-preparedness indices, which aim to measure health security capacity, were not meaningfully associated with standardised infection rates or IFRs. Measures of trust in the government and interpersonal trust, as well as less government corruption, had larger, statistically significant associations with lower standardised infection rates.

High levels of government and interpersonal trust, as well as less government corruption, were also associated with higher COVID-19 vaccine coverage among middle-income and high-income countries where vaccine availability was more widespread, and lower corruption was associated with greater reductions in mobility.

If these modelled associations were to be causal, an increase in trust of governments such that all countries had societies that attained at least the amount of trust in government or interpersonal trust measured in Denmark, which is in the 75th percentile across these spectrums, might have reduced global infections by 12·9% (5·7–17·8) for government trust and 40·3% (24·3–51·4) for interpersonal trust. Similarly, if all countries had a national BMI equal to or less than that of the 25th percentile, our analysis suggests global standardised IFR would be reduced by 11·1%.

Interpretation

Efforts to improve pandemic preparedness and response for the next pandemic might benefit from greater investment in risk communication and community engagement strategies to boost the confidence that individuals have in public health guidance. Our results suggest that increasing health promotion for key modifiable risks is associated with a reduction of fatalities in such a scenario.

Funding

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, J Stanton, T Gillespie, J and E Nordstrom, and Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Research in context

Evidence before this study

Responsive policies such as physical distancing and mask mandates were important in shaping outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, the conditions associated with cross-country variation in infection and fatality rates during the COVID-19 pandemic are not well understood. In the aftermath of the 2013–16 Ebola epidemic in west Africa, WHO launched a voluntary Joint External Evaluation (JEE) process to track adoption of core capacities required under the 2005 International Health Regulations and to assess national capacity to prevent, detect, and respond to disease with potential for pandemic spread. WHO’s April 2021 interim assessment did not find JEE scores from the 100 countries that had conducted voluntary assessments to be correlated with COVID-19 outcomes, although such metrics were designed as benchmarking exercises for National Action Plans rather than cross-country comparators. Preliminary analysis of COVID-19 outcomes in relation to other health-system capacity indices, such as the Global Health Security Index and the index of effective coverage of universal health coverage produced by the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) have also been found not to be predictive of COVID-19 outcomes. Other exploratory research on COVID-19 outcomes has had a regional focus or has focused on a small number of country experiences.

Added value of this study

We analysed measures of pandemic preparedness. 12 indicators of preparedness and response and seven indicators of health-system capacity were considered, in addition to ten other demographic, social, and political conditions that previous research suggests might be relevant. Associations with both incidence and mortality from SARS-CoV-2 infections were investigated. We controlled for demographic, biological, economic, and environmental variables associated with COVID-19 outcomes, including population age structure and environmental seasonality, population density, national income, and population health risks, to identify contextual factors subject to policy control. This research considerably expands on the scope of previous research by investigating correlates of pandemic preparedness and mitigation in 177 countries between Jan 1, 2020, and Sept 30, 2021, and includes inputs that have been adjusted for problems associated with under-reporting of COVID-19 outcomes. This expanded scope was possible because of inputs from COVID-19 research produced by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation and mortality and population estimates generated by GBD.

Implications of all the available evidence

The existing metrics for health-system capacity and national pandemic preparedness and response have been poor predictors of pandemic outcomes, suggesting other areas might merit greater weight in future preparedness efforts. Not all of the correlates that account for some variation in infections per capita and infection-to-fatality ratios, such as age structure, altitude at which a population lives, and environmental seasonality, are easy for policy makers to control. Yet, other factors are within the policy realm, including preventive health measures focused on population health fundamentals: encouraging healthy bodyweight and reducing smoking might be helpful in averting morbidity and mortality in future pandemic scenarios. Moreover, the level of trust is something that a government can prepare for and earn in a crisis, and our analysis suggests doing so may be crucial to mount a more effective response to future pandemic threats. Large unexplained variation in differences in SARS-CoV-2 infections across countries speaks to the importance of further research in this area.

::::::

medRxiv

This article is a preprint and has not been certified by peer review [what does this mean?]. It reports new medical research that has yet to be evaluated and so should not be used to guide clinical practice.

Ethnic disparities in immunisation: analyses of zero-dose prevalence in 64 low- and middle-income countries

Bianca Oliveira Cata-Preta, Thiago Melo Santos, Andrea Wendt, Daniel R Hogan, Tewodaj Mengistu, Aluisio Jardim Dornellas Barros, Cesar Gomes Victora

medRxiv 2022.02.09.22270671; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.09.22270671

Posted February 10, 2022.

Abstract

Background The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) recommend stratification of health indicators by ethnic group, yet there are few studies that have assessed if there are ethnic disparities in childhood immunisation in low and middle income countries (LMICs).

Methods We identified 64 LMICs with standardized national surveys carried out since 2010, which provided information on ethnicity or a proxy variable and on vaccine coverage; 339 ethnic groups across the 64 countries were identified after excluding those with fewer than 50 children in the sample and countries with a single ethnic group. Lack of vaccination with diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus (DPT) vaccine, a proxy for no access to routine vaccination or zero-dose status, was the outcome of interest. Differences among ethnic groups were assessed using a chi-squared test for heterogeneity. Additional analyses controlled for household wealth, maternal education and urban-rural residence.

Findings The median gap between the highest and lowest zero-dose prevalence ethnic groups in all countries was equal to 10 percentage points (interquartile range 4-22; range 1 to 84) and the median ratio was 3.3 (interquartile range 1.8-6.7; range 1.1-30.4). In 35 of the 64 countries, there was significant heterogeneity in zero-dose prevalence among the ethnic groups. In most countries, adjustment for wealth, education and residence made little difference to the ethnic gaps, but in four countries (Angola, Benin, Nigeria, and Philippines) the high-low ethnic gap decreased by over 15 pp after adjustment. Children belonging to a majority group had 29% lower prevalence of zero-dose compared to the rest of the sample.

Interpretation Statistically significant ethnic disparities in child immunisation were present in over half of the countries studied. Such inequalities have been seldom described in the published literature. Regular analyses of ethnic disparities are essential for monitoring trends, targeting resources and assessing the impact of health interventions to ensure zero-dose children are not left behind in the Sustainable Development Goals era.